The Art of Note-Making

I’ve been thinking a lot about Personal Knowledge Management lately and the path information takes as it enters and exits my PKM system, and I’ve noticed that information tends to fall into one of three buckets:

- Things I may need to reference

- Tasks I will need to do

- Ideas I want to develop

The first two are pretty straightforward — I simply capture those into the appropriate bucket. For a long time, I used Evernote as my reference file and OmniFocus as my task list. When COVID-19 happened and I reworked my system, I found a lot of value in having everything in one place. So now, I keep reference material and tasks in the same bucket as the ideas I want to develop. This has a lot of benefits, but I’ve also discovered I can’t treat all my notes the same. I have a separate, more active system for developing my ideas. It’s quite a bit more involved, but I believe it’s worth it.

In this article, I want to consider the difference between my old note-taking workflow and the note-making that helps me so much in the creative process.

What is Note-Making?

I first heard the term note-making from Nick Milo, who has an excellent YouTube channel called Linking Your Thinking. (He also runs an excellent workshop that I have gone through as a paying customer.)

The basic idea of note-making is that you don’t simply capture your notes and dump them in a library somewhere. Instead, you work on your notes and update them over time. Instead of simply taking notes, you are crafting them. Your approach is like that of a skilled craftsman, who knows that within the chunk of wood or stone lies a beautiful carving. You can’t see it at the beginning, but as you continue to refine the material you’re working with, you start to see it come through.

To the note-making craftsman, a tool like Obsidian is more of a workbench than a filing cabinet. It’s not a place where you hold things until you need them; it’s a place where a magical transformation happens. It’s where you work your craft and refine your ideas as you turn them into something special worth sharing.

The end result is something that reflects your current thinking on a topic, comprised of useful facts and information as well as your own opinions on the topic. Something much more beautiful than simply a captured note. Nick calls this type of note a Map of Content (or MOC), and describes your role in crafting it as that of a cartographer.

This analogy immediately resonated with me as I had just finished reading The Great Mental Models, Volume 1 where one of the models described is The Map is Not the Territory. You see, whenever you see a map, what are you actually seeing is an opinionated interpretation of what the mapmaker (cartographer) considered important enough to include. There’s no way you can include all the information in a map, so the cartographer is forced to make decisions about what’s important, and what’s not.

As you collect notes on a topic, you will eventually get to a point where you feel overwhelmed by everything you’ve collected. That is the point where you assume the cartographer role and go back to your workbench (MOC) as you craft your thoughts through intentional note-making.

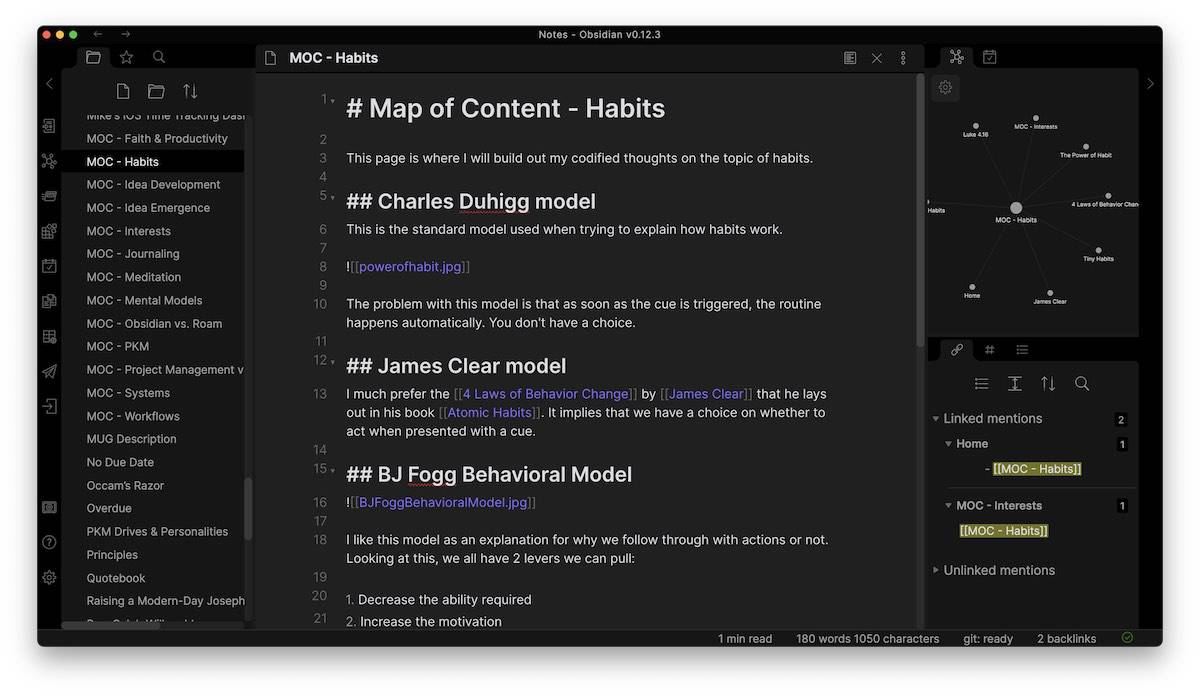

Let me give you an example of a MOC from my own Obsidian vault.

This is my MOC on the topic of habits:

In this note, there are several things:

- A note at the top as to why this MOC exists.

- A section on the standard habit loop (and image) presented by Charles Duhigg in The Power of Habit.

- An opinion about why I don’t like this definition.

- A section on James Clear’s 4 Laws of Behavior Change from Atomic Habits and why I like this better.

- A section on BJ Fogg’s Behavior Model (and accompanying chart) from Tiny Habits.

- A section with some links to additional resources/notes that speak to this topic.

- A section on Bible verses that speak to the topic of habits.

Every time I add a note to Obsidian about habits, I look at this MOC and see what I want to add or update. As a result, this note is in constant development and continues to get better and better over time. And I’ve found that as I force myself to make this note better every time I touch it, my thoughts on the topic continue to gain clarity. The process of forcing myself to add opinion notes and decide on what’s important helps me to better understand the topic.

Note-Making vs. Note-Taking

As I consider my new note-making workflow with the traditional note-taking practice, I notice there are several important differences.

First, note-making assumes that your notes are living things. While note-taking, captured notes are static and never change. But with note-making, your notes are dynamic and are constantly being updated and refreshed.

As a result, note-making means your notes are never etched in stone. With note-taking, your notes are finished when they are captured and added to your library. They are there so you can find them if you need them, but they aren’t really doing anything while they sit in storage. With note-making, your notes are in active development. Each note you make is a reflection of the sum total of notes you’ve collected, and the value is in the relation to your other notes.

With note-making, relationships are important. Note-taking focuses solely on the content of the active note, but note-making considers the connections to other notes. Note-making recognizes the fact that each note is influenced by the other notes in your library, and takes into consideration the value of previous thoughts and ideas.

The fundamental approach to your notes is completely different with note-making. Instead of trying to collect everything that you think might be useful someday, you’re focused on understanding as much as you can from the ideas that you already have.

I talked with David Sparks about this on a recent episode of Focused, and he described the difference in mindset as the dragon and the jeweler. The dragon tries to horde things and sits on top of the diamonds so no one else can get them, but the jeweler is actively working on his diamond so he can make it even better. The dragon may accumulate a lot but doesn’t do anything with it. The jeweler is the one who is getting the real value from working with what they already have.

A Couple Tips for Making Note-Making a Habit

Here’s a couple of quick tips I’ve learned about note-making over the past several months that could help you develop a jeweler’s mindset and find more diamonds.

More Signal, Less Noise

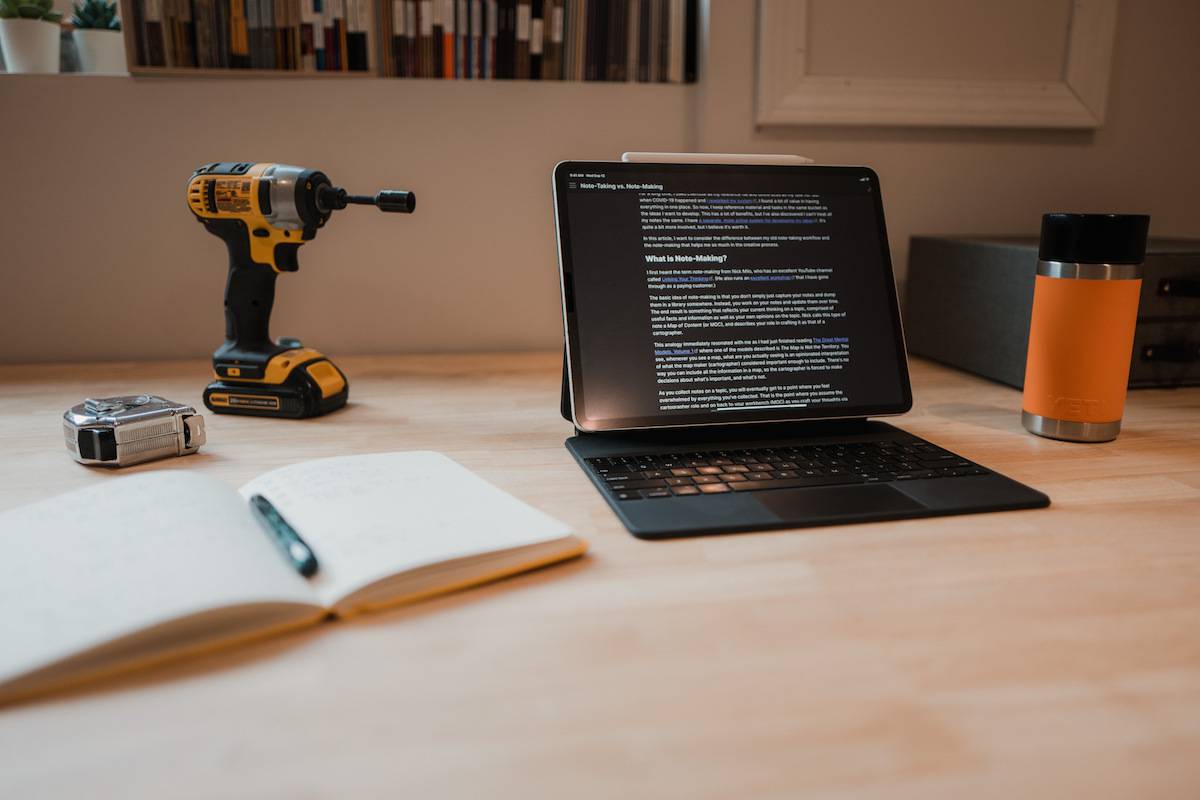

I’ve intentionally set up my note capturing system so that it doesn’t just automatically add everything to my Obsidian vault. I capture notes in two places:

- My fancy notebook

- Drafts on my iPhone (and occasionally Apple Watch)

At the end of the day, I transfer things over as part of my shutdown routine. This forces me to manually add the notes that I capture to Obsidian, and adds another review step where I can filter out any notes that I don’t really want.

The key here is that I am ruthless about cutting things here. I estimate about four out of every five things I capture never makes the cut and gets transferred to Obsidian.

The more distance I get between the moment I capture my idea, usually the less excited I am about it. Every idea seems great when you have it, but not every idea is a good one. By making myself wait, I increase the quality of the ideas that actually end up being developed in Obsidian.

This is really the key. I’d rather five really great ideas than 500 mediocre ones. When it comes to ideas, quality beats quantity.

Don’t Link Everything

As your notes library grows, resist the urge to link everything. Bidirectional linking is a really powerful concept but loses value if it’s overused. For example, if I have a note called “Habits,” My Unlinked Mentions will show me every use of the word “habits” in my entire vault. You can turn any of these into a Linked Mention by clicking the Link button, but resist the urge to do so! You don’t want every mention of the term “habits” to show up, you want only the best ones.

I wrote recently about the power of Obsidian’s local graph and how I use it to navigate my notes, but if every page has 100 linked mentions, it’s difficult to see which ones really matter. Just like the notes themselves, you want quality over quantity here.

Don’t Judge Your Work

As you see examples of others’ work, don’t compare the results of your note-making practice with anyone else. Your notes are a reflection of your personal journey. Your Habits MOC may look completely different than mine, and that’s the point! Add your own opinions and don’t try to be someone else. The more authentic your notes are, the more value they have.

If you’re unhappy with the output, then change the input. Your brain is always connecting things, so the place to make improvements is to give it better dots to connect. But remember, quality matters more than quantity. Read more books, but don’t try to recreate every argument the author makes. Capture the things that stand out to you, then spend some time thinking about them and figure out how and why they matter.

Automate Your Review

Note-making requires that you look at your notes frequently. I do this as I process my notes in Obsidian, but I still find some of my MOCs don’t get much TLC.

One thing that makes reviewing and updating notes easier is the Review plugin. (You can also install this in Obsidian by going to the Settings, clicking Community Plugins, and browsing for Review.) Once installed, you can access the Command Palette by using the keyboard shortcut Command – P and selecting the Add this note to daily note for review option. Select date (the Natural Language Dates plugin allows you to use terms like tomorrow, next week, etc.) and a Review section will be added to that daily note with a link to your current note. Then when you go to your daily note on that future date, you can just click the link to review your note and make any necessary changes.