Cultivating and Connecting Using Modular Notes and Personal Memos

The act of creating is a tricky thing. It requires intense focus, connective thinking, and an appropriate risk appetite to put your creation into the wild.

Advising is a little different, though there are a lot of connections to the act of creating. Advising requires intense empathy — a willingness to understand the client’s situation. Advising requires creativity in its own regard — unique problems require unique solutions. Finally, depending on the profession, a great deal of advising comes from past experience and precedent. The more often you’ve encountered the problem in the past, the more likely you’ll rely on the past for a solution.

Given that context, my continued adaptation of Mike Schmitz’s Creativity Flywheel has taken a few lefts and rights. My needs are different than Mike’s and so I have a different workflow. Different strokes for different folks, after all.

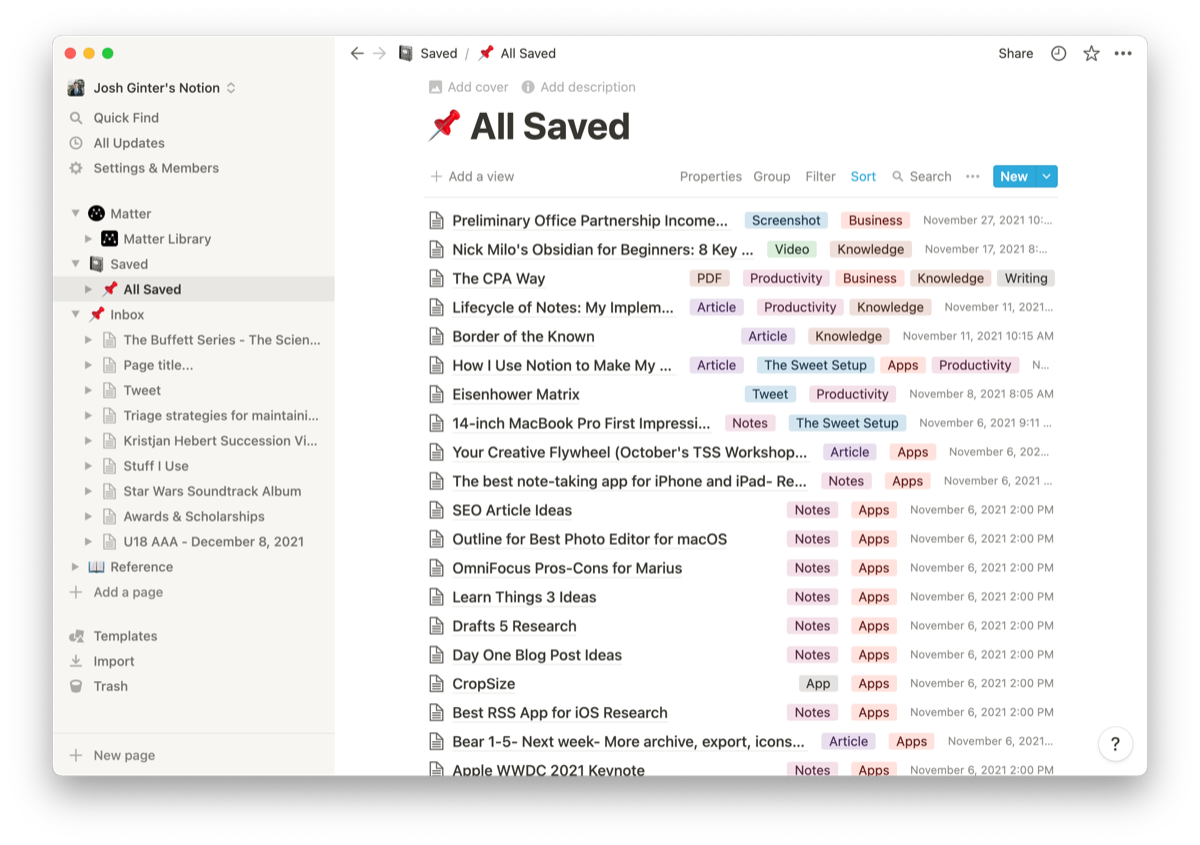

A few weeks back, I dove into how I capture and curate information. It’s pretty simple, really — everything goes into a list in Notion and I then tag and store anything I want to keep for the long run in a separate Notion database.

Today, I’ll show how I’ve adapted Mike’s “Cultivate” and “Connect” steps into something I can use to help advise clients each day. It’s not a 1:1 adaptation, but I’ve been surprised by how many similarities have popped up.

Cultivating Personal Memos

Mike’s cultivation analogy is pretty good: If you imagine a gardener who tills the soil in a flowerbed and apply that to tilling and pruning your notes and captured information, you’re on the right track.

This is the step of the Creativity Flywheel I find most difficult to adapt. It takes purposeful intent to revisit your long list of notes and re-read and unearth old information. The pull of new information usually outweighs the drag of old information for me.

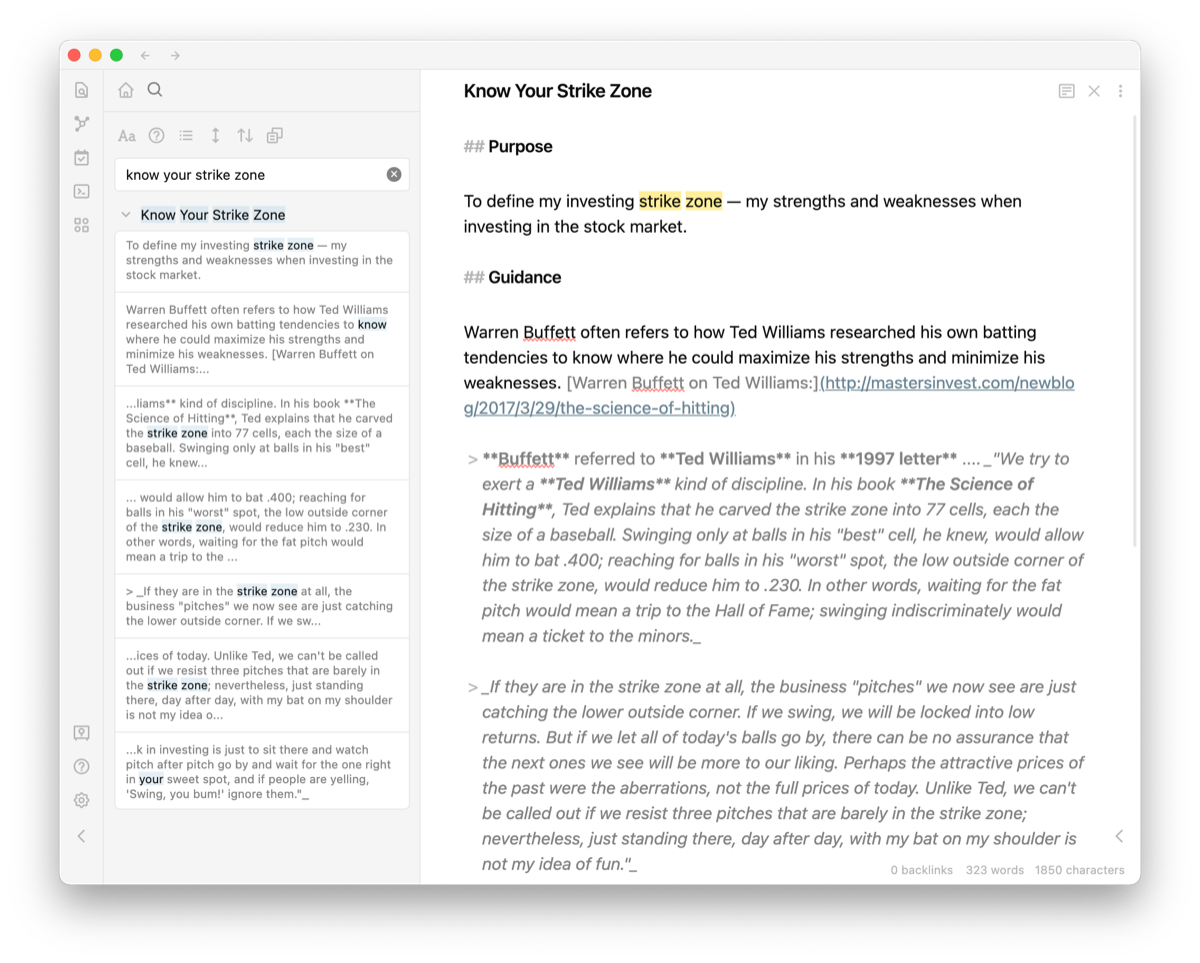

To get around this, I’ve adopted a process of writing short memos to myself. Each short memo has a consistent outline and captures a specific thought. The goal of each memo is to come to a quick conclusion on a topic before using the conclusion to connect to the next topic. I try to keep them to no more than 200 words of my own writing.

The consistent outline for each memo is as follows:

- Purpose/Issue — This is a one sentence description of the memo’s raison d’être or the problem I’m trying to solve. For example, a purpose may be “To determine the best method to capture information in Notion.”

- Guidance/Analysis — This is the body of the memo and holds both my thinking and links or quotes from others. In building out this section, I tend to rely on captured and curated information in my Notion archive first, followed by general internet research thereafter. I work to keep this section no more than three points long. If the problem requires more analysis, it’s likely best to break down the issue further into more memos. If it doesn’t require more analysis and a better piece of guidance pops up, I’ll replace the weakest point of guidance.

- Conclusion — This is a one, maybe two sentence wrap-up with a summarized solution and the next best step forward.

Now, I recognize that “memo” is a scary word. CPA school drilled memo writing into candidates, so I’m used to the term, the format, and the purpose of a memo.

I love short memos. They are clear and succinct. They are very easy to write, but your mileage may vary.

Further, the process of writing a short 200-word memo is probably beyond Mike’s “cultivation” vision — the purpose of cultivating is to stir up information and search for new connections. My choice to create a short memo with an introduction, body, and conclusion is probably more “into the weeds” than he imagined. Writing a short memo forces the act of stirring up old information. It works for me and produces nice bite-sized blurbs of structured thinking that I can use to build out solutions for major problems.

I do all this memo writing and storage inside Obsidian, of course. Each memo is a building block for connective thinking. Powerful connective note-taking apps like Obsidian and Roam Research make short of work of both the writing process and the discovery/connective process in this workflow.

Connection, Or What I Call Modular Note-Taking

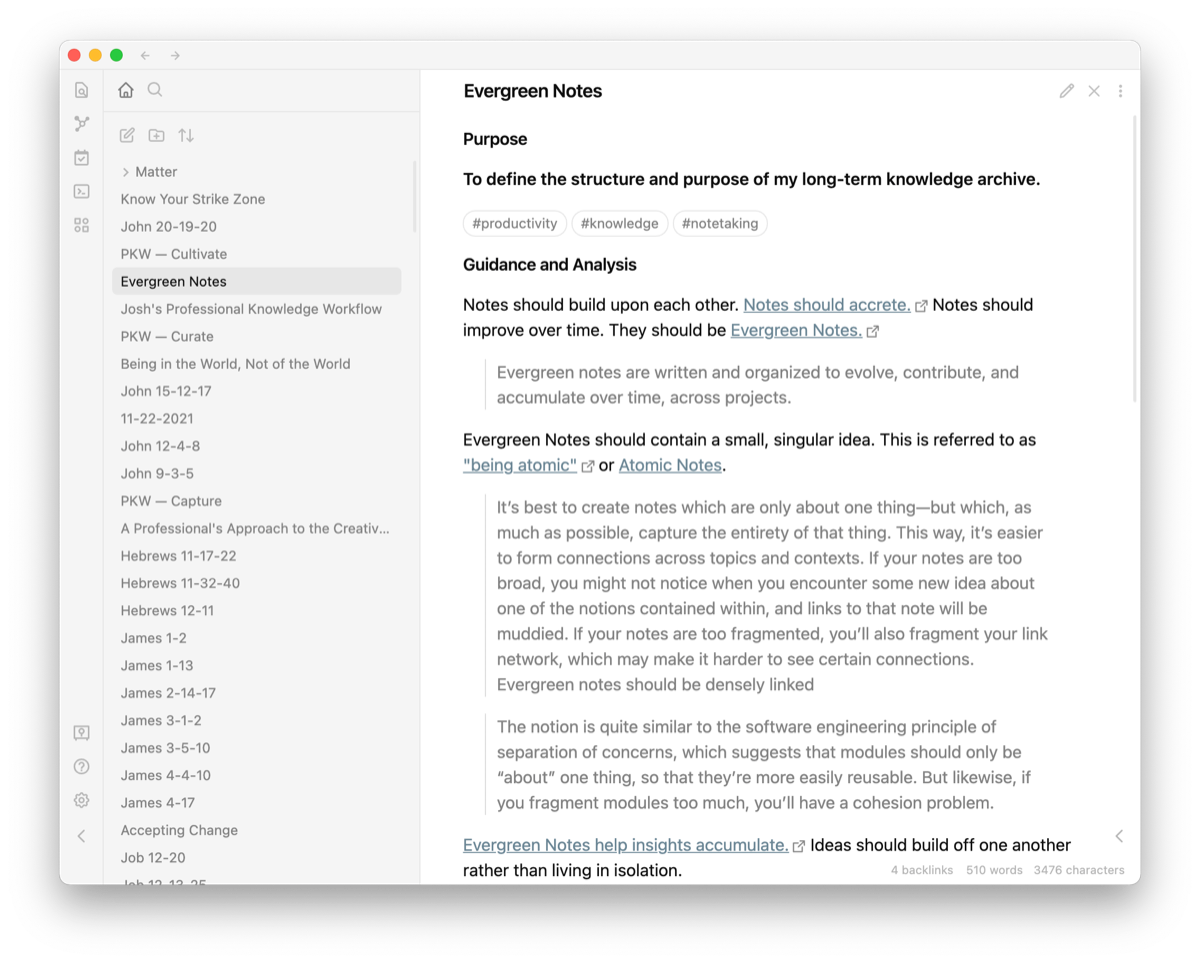

Why do I keep each of these memos short and bite-sized? Because the more broken down the topic, the more easily I can take that memo and apply its conclusion to a bigger problem.

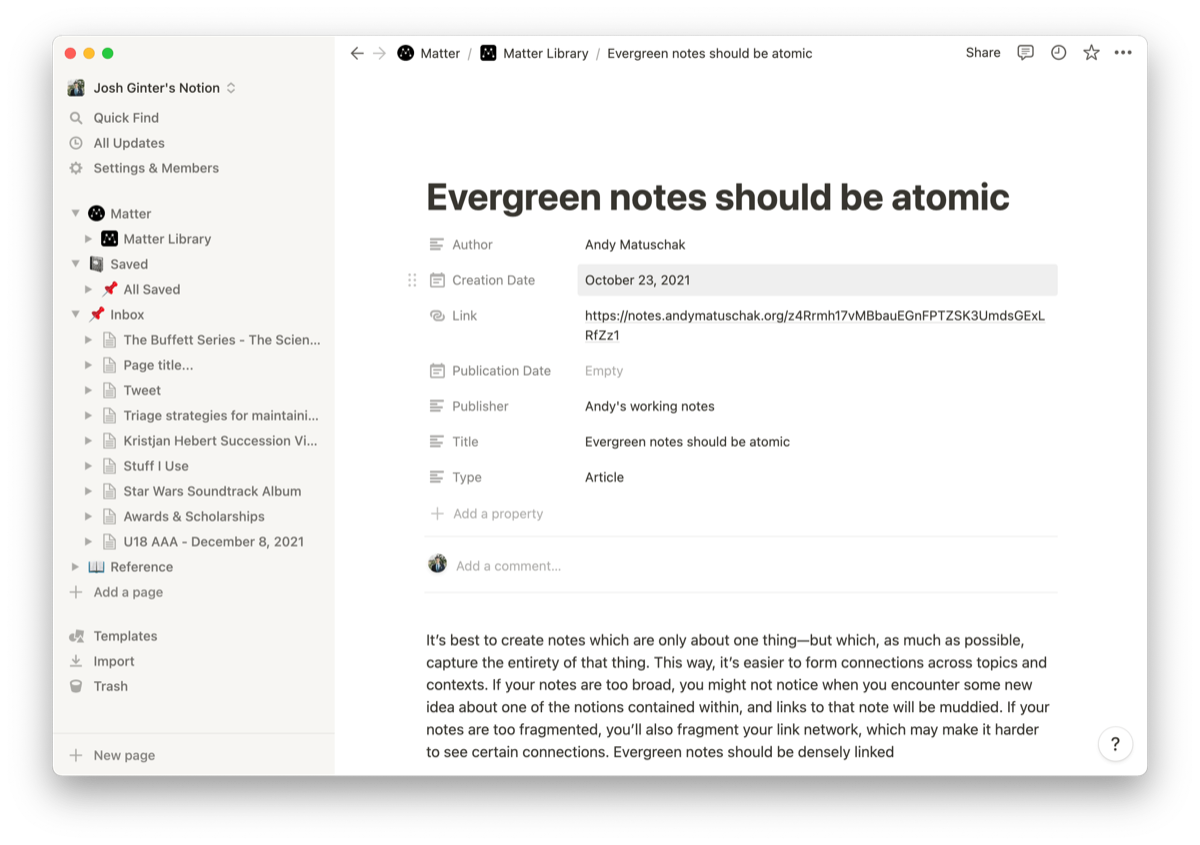

This is by and large Andy Matuschak’s point when he discusses why notes should be atomic:

It’s best to create notes which are only about one thing—but which, as much as possible, capture the entirety of that thing. This way, it’s easier to form connections across topics and contexts. If your notes are too broad, you might not notice when you encounter some new idea about one of the notions contained within, and links to that note will be muddied. If your notes are too fragmented, you’ll also fragment your link network, which may make it harder to see certain connections.

Take, for example, a corporate restructuring. It takes 10 years of schooling in Canada and 10 to 15 years of experience to handle an accounting and tax problem like this, so I won’t pretend to be an expert. But a corporate restructuring is a complex undertaking and has many individual issues that need to be addressed along the way. There may be an acquisition of control, a business combination, a share sale, a capital gains exemption, and GST issues to handle. Each of these problems consist of their own itemized issues as well.

To handle such a task, I might create a larger project document inside Obsidian that acts mostly as a table of contents. My projects have the same outline (Purpose/Guidance/Conclusion) as personal memos.

- The Purpose simply states the end goal of the situation. Example: “To restructure the corporate affairs of XYZ Company.”

- The Analysis section then gets broken down into the major issues undertaken (example: acquisition of control, capital gain, etc.), which are then broken down into more granular issues, which are then referenced to the small memos I’ve already written on the topic.

- The Conclusion will provide the necessary steps to undertake to complete the project. Example: “John Smith will sell shares of XYZ Company to Jane Doe for $1 million on January 1, 20X5, triggering a capital gain with exemption, an acquisition of control and a new tax return”.

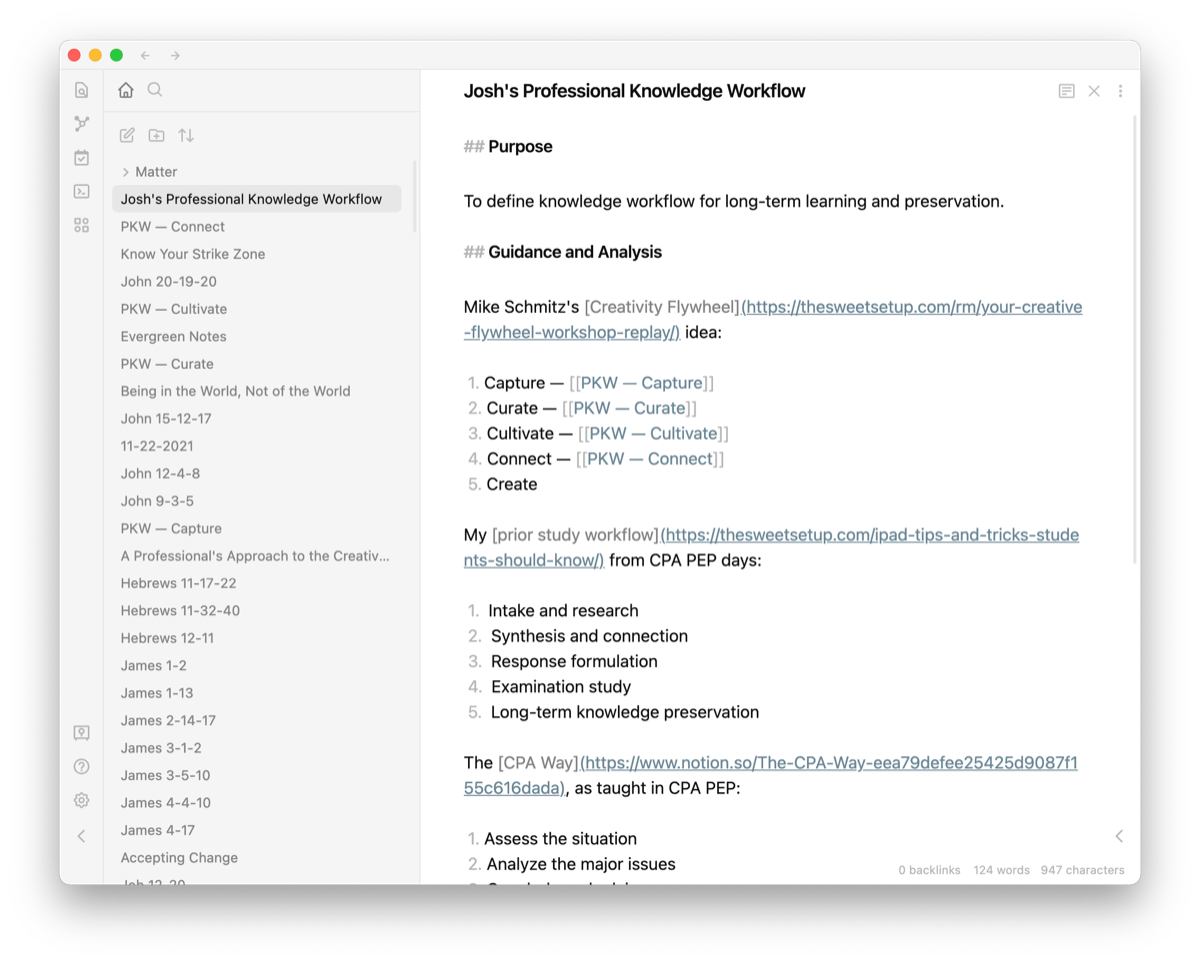

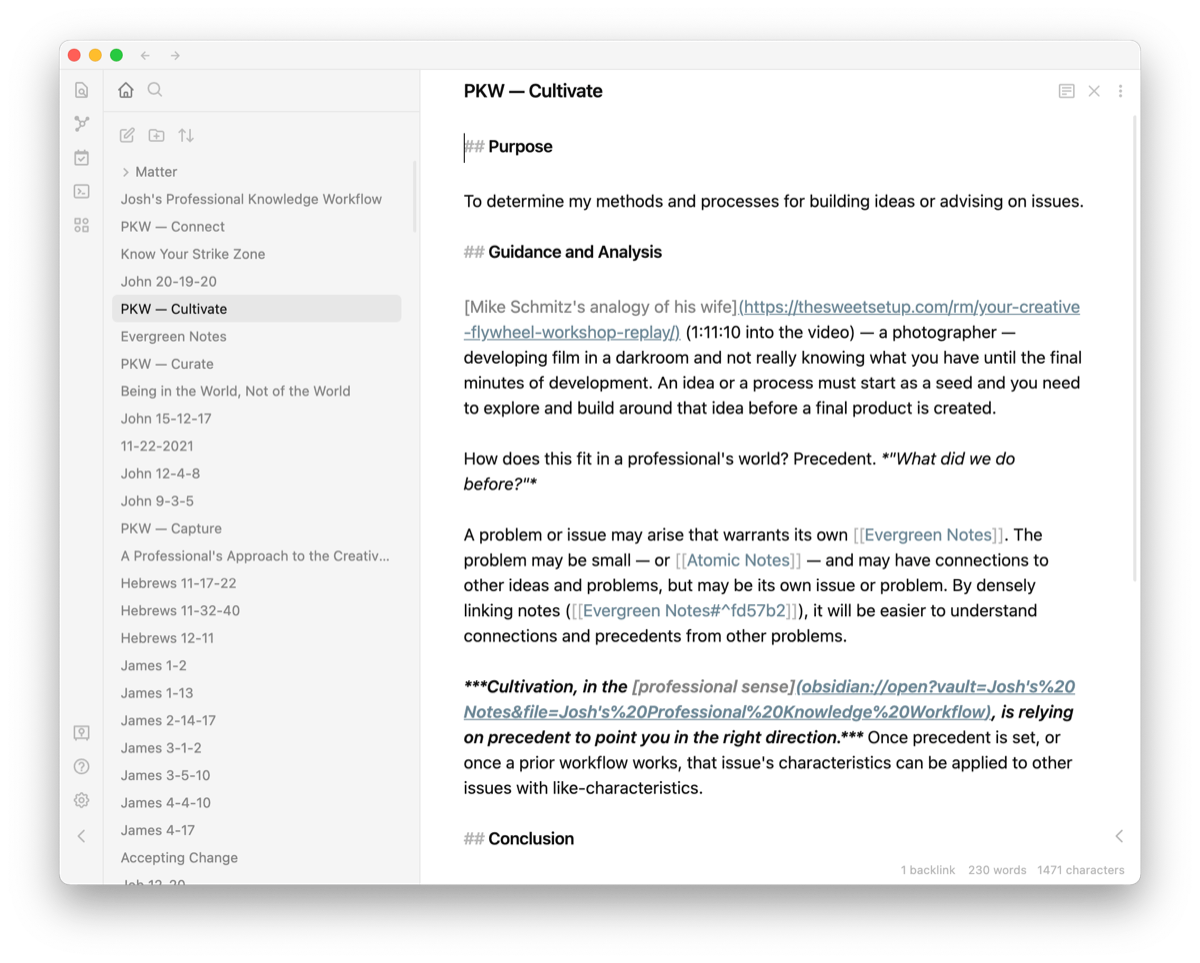

So, here’s a quick example of how those short modular memos I wrote in my cultivation step end up inside a larger project. This project actually showcases some of my process in regards to building out this very workflow. You’ll note I haven’t completed the whole thing just yet.

As you can see, this project is by and large a table of contents. The analysis section is riddled with links to other bite-sized memos in Obsidian, which themselves are riddled with links to other memos and quotes stored in Obsidian.

You can see here how quickly connections grow across notes, quotes, memos, and projects. Assuming I properly write out these short memos and document the steps the I took to solve each problem, I can use the resulting solution across any range of new issues or projects I come across in the future. A small, unrelated solution 10 years ago may be the key to unlocking an entirely new solution today. By keeping these memos small and modular, it’s significantly easier to build out a solution for a bigger project.

Turning Your Knowledge Archive into a Passive Investment

Whereas home builders work with their hands and a saw and hammer, we accountants work with our brains and a computer (and Excel spreadsheets). A home builder can build a home that they subsequently rent out for passive income. My assumption has always been, then, that a knowledge worker could build out some sort of library that can also produce passive income.

This is the ultimate goal of this workflow: To build a library of knowledge that can be quickly searched, itemized, and processed to discover new solutions for new problems.

Ideally, anyone could use this library to uncover solutions to problems they would otherwise be unable to solve. As long as it’s built properly, of course.

Better yet, someone new could come along and add their expertise to my library.

If a client walks through the door on a whim and asks a specific question about a specific detail in their file, chances are you can’t remember the exact answer on the spot. Once your head is into a specific problem, you know it like the back of your hand. Six months later, it’s hard to recall every specific detail.

Modern computers and apps like Obsidian or Roam Research enable connective thinking to reach a new level. Today, you can document your brain’s processing of a solution and use connective apps like Obsidian to connect that processing to other problems that you worked on decades ago. These sorts of apps unlock solutions that span across time in ways we could have never imagined 20 or 30 years ago.

Computers have long been good for capturing, curating, and storing information. As they evolve, former brain processes of cultivating and connecting are inching over to computers as well.

May as well take advantage of that evolution.