Matt Gemmell’s Ulysses Setup

Matt Gemmell is a writer and author living in Edinburgh, Scotland.

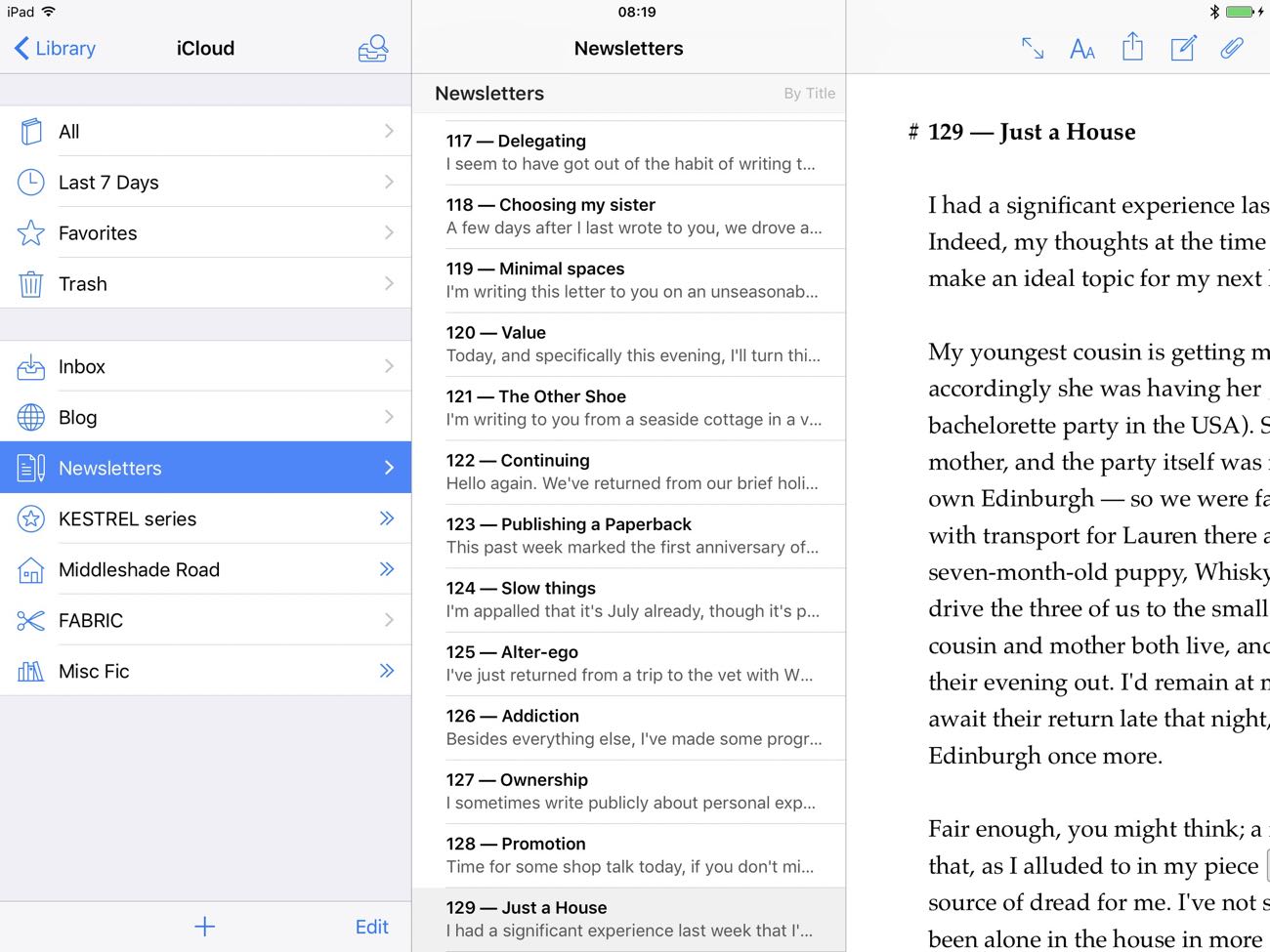

I’m a fairly recent convert to Ulysses — eight months ago — but I’ve moved over to it fully. I previously used Editorial for blog articles and my weekly newsletter for site members, and Scrivener for long-form fiction, such as my novels. I use an iPad Pro full-time, so I’m always talking about the iOS version of each app.

For most of 2017, though, I’ve done all my writing in Ulysses. I don’t file projects by state or progress, except that if I’m currently working on something and it’s a standalone piece (i.e. it doesn’t fall into any larger project), it’ll be in the Inbox. Beyond that, I keep everything in top-level groups or projects. They’re broadly split into five categories:

- Site articles

- Weekly newsletters

- Book series

- Standalone books

- Miscellaneous shorter works of fiction (which are often writing exercises)

I’ve developed a filing system I use within a given fiction project, which involves a series of groups at the root of the project:

-

Requires Attention. This is actually a Ulysses filter, which matches sheets which satisfy any of the following criteria: have the “todo” keyword; contain the text “XXX” (which I use as a fill-me-in-later placeholder); or containing any kind of annotation. This makes the editing process much easier, since I can see what’s still to be done, all in one place.

-

Journal. I keep diary entries about significant thoughts or realisations regarding the project. This isn’t my master list of ideas or plans, but rather an actual journal that accompanies the work and gives behind-the-scenes insight into the creative process. It’s useful to me, and it’s also a future perk for members of my site.

-

Front Matter. The book’s front matter goes here, unsurprisingly. Author bio, dedication, title page, copyright, half-title, and the jacket blurb which I insert at the front of ebook versions, since it’s easier to access there.

-

Manuscript. This is where the action happens, and is the only group which will have a word target. It’ll be further subdivided into Chapter folders, but only once the first draft is complete. I write in scenes — one per sheet — and assemble chapters later, based on rhythm and feel. For my thriller novels, I’m fond of using Parts too, so that’ll sometimes be the top-level organisational structure within the Manuscript folder. In either case, there’ll potentially also be a Prologue and Epilogue there too.

-

Back Matter. The book’s back matter; usually an Afterword, and an Acknowledgements section.

-

Notes. Any and all work-in-progress notes I might need. A common type of note is a timeline of some kind, and I also keep my own question-and-answer documents about plot points, to refer back to. Another frequent entry is a list of time-zones, and travel times between them, so that I can keep track of plausible times of day and night as my characters travel all over the world.

-

Characters. I religiously keep character sheets up to date. They include physical descriptions, backgrounds, mannerisms, and important points of relevant context for series books.

-

Locations. A sheet for each significant location, if it requires detailed explanation of its own. These often include photos. I try to visit as many of my locations as possible before using them, or at least places which inspired them.

-

Research. This covers anything that’s not in Locations. For thrillers, it’ll often be technical overviews for things like vehicles, weapons, and technologies — real or imagined.

-

Cover Design. I even keep my communications with my cover designers in Ulysses. I write the initial brief there, and then follow-up notes on changes I’d like made. It’s easier to do it where I can refer to the rest of the work for specifics on settings, moods, and so on.

-

Unused Scenes. This is a habit from my years of using the excellent Scrivener. Whenever I decide that a scene doesn’t make the cut, or needs to be rewritten, I put the old one here instead of deleting it. It’s occasionally useful for resurrection later, but mostly it just makes for a fascinating archeological look at the differences between the initial draft or plan and the finished story.

In terms of my writing setup, I of course write solely on the iPad Pro (though I do proof-read on my iPhone). I keep it in landscape orientation, and I type on a Magic Keyboard. Ulysses is always running with the current sheet full-screen, unless I temporarily have the Notes sidebar open to refer to something. I make my master plot outlines in OmniOutliner, then I copy the relevant part into a note in the current sheet, and work from there.

I use keyboard shortcuts for everything, and try not to touch the screen unless I have to. I always use Quick Open (Command+O) to navigate between sheets, or the Command-1/2/3 shortcuts to show Ulysses’ various panes.

My preferred editor typeface is Palatino, which I also set my books in, and my editor theme is my own, called Gemmell Two. It supports both light and dark modes, but I only tend to switch between them once every few weeks, as the mood takes me.

It was a big adjustment at first, coming from Scrivener’s rich-text, typeset environment, but I’d used Markdown for years with my blog articles so it was just a matter of accepting that I could use it for fiction too. I’ve now come around to the idea of keeping content and presentation entirely separate, and I greatly appreciate that Ulysses can produce ebooks as well as PDFs right from the iPad, whereas Scrivener currently requires the Mac version to create ePub files in one go.

I’ve recently made a concerted effort to reduce clutter from my life, and focus on a small set of well-made tools to let me do my work, without extraneous elements or distractions. Ulysses fits well with that philosophy. In terms of hours spent in it, it’s the most-used app on my iPad.